Do you feel squats in your lower back more than your quads? Do you lean forward or struggle to reach depth? Do you have the dreaded “butt wink”? While there are a lot of potential causes for these differences in movement, what might feel like you just “sucking” at squats could be based on your anatomy.

The same squat position does not work for everyone. I’m sure this is a surprise (sarcasm alert) but people are built differently. In this article we will be looking at anatomical restrictions to the squat, basically, HOW you’re built. We will evaluate how your body proportions and hip anatomy may impact your ability to squat and what you can do about it.

Surprise Physics!

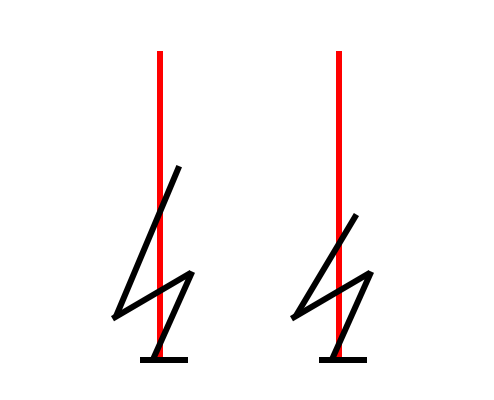

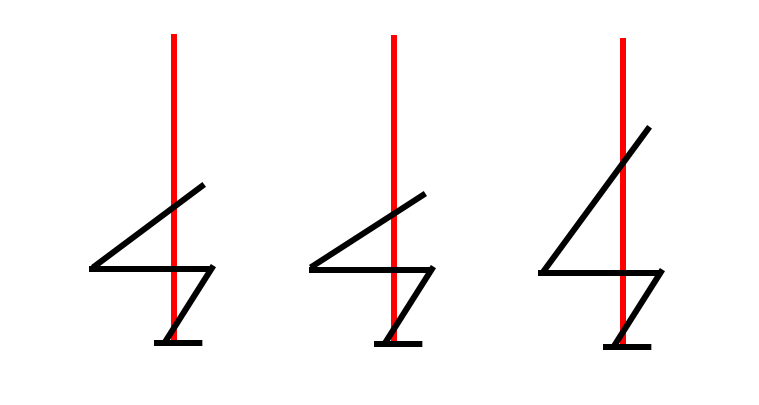

Weightlifting is nothing more than physics applied to the squishy human form, and your body is just a series of biological levers. An important concept is the line of force, which runs vertically up from about your midfoot, through the center of your base of support.

Everything occurs around this line. Go too far one way or the other and you’ll end up on the floor. This idea of levers and line of force is a topic for a different, much longer, article but understanding the basic principle is important.

Proportions

There are 3 levers we need to look at when assessing proportions for your squat: floor-to-knee (tibia), knee-to-hip (femur), and hip-to-shoulder (torso). While each individual lever is important, the most important thing to look at is your overall proportions.

Example 1: Long shin, short (or similar) thigh

If your floor-to-knee length is long, or similar, when compared to your knee-to-hip, you will be able to keep a more upright posture and achieve a deeper squat with the SAME degree of ankle dorsiflexion as someone else.

This person will feel squats more in their quads while sparing their lower back. If they have a long hip-to-shoulder lever, they’re even better off.

This is the person who can reach perfect depth while maintaining a completely upright posture and thinks squats are the most fun thing to do.

Example 2: Short shin, long thigh

If your floor-to-knee length is short compared to your knee-to-hip, you will need to lean forward during your squat to maintain balance over your base of support as you get lower.

Someone with this type of bony anatomy will often say that they feel squats in their lower back. They will also struggle to squat below parallel and will often say they cannot go any lower or that they feel like they are going to fall, even though they still have ROM available in their ankle, knee, and hip.

If this person has a short hip-to-shoulder, it makes the problem worse.

What can I do?

The best way to overcome your proportions is with a change in squat width. The wider your feet go, the shorter the forward-to-backward (anterior/posterior) length of your knee-to-hip lever becomes, relatively.

This changes how far backward the butt goes, which allows for a different trunk position and changes the forces you will feel on your hips, quads, and back.

A small increase in width can have a big change on how your squats ‘feel’. Test different width squats and reassess.

KEY POINT: make sure your knees do not collapse inwards as you squat. Regardless of your stance width, your knees should track towards your toes at all times during the squat.

Hip/Femur Anatomy

If proportions aren’t your problem, it could be your hip/femur anatomy.

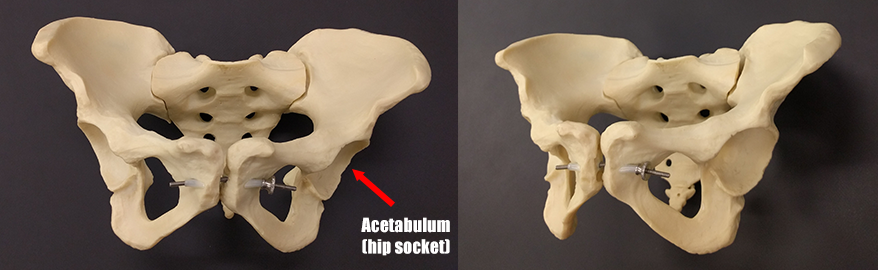

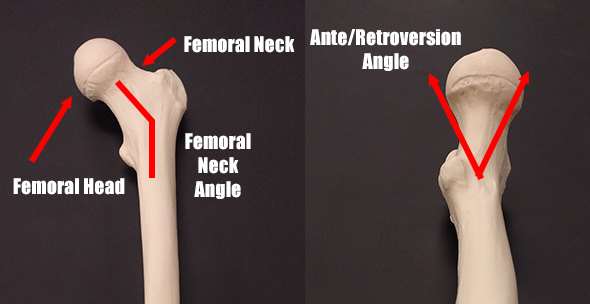

The hip is a “ball-in-socket” joint, with the top of your femur (the “ball”) fitting into your pelvis (the “socket”).

Just like we all have different levers, the shape and angle of both the ball and socket vary from person to person, and how this joint comes together can have a dramatic effect on your ideal squat stance.

If you have a deep hip socket, one the points further backward, or both, you will most likely need a wider squat stance. Similarly, if your femur points further backward, the femoral neck is short, or the femoral neck angle is more obtuse, you will also need a wider squat.

This is necessary because the backward angle, deeper socket, shorter neck, and/or more obtuse neck angle result in bone-on-bone contact sooner than for someone without these anatomical variations.

This bony contact is not only uncomfortable, but it is a common cause of the dreaded butt wink.

No, your butt wink probably has nothing to do with how tight your hamstrings are. Once there is bony contact, your hip can’t actually flex any further. Since the hip is blocked, this motion needs to come from somewhere else as you continue to lower yourself, which is generally your lumbar spine.

Finding your appropriate width will make squats more comfortable, increase loading of the correct muscles, and most likely eliminate your butt wink. This will not only make you stronger but it will decrease your risk of future lumbar and SIJ pain.

If you want to know how to assess your hip and other soft tissue restrictions to your squat, tune in for the next part of my squat series.

Questions or comments? Drop me a line below or send me an email.

POST REPLY